In This Story

It’s not every day students get to visit a Biosafety Level-3 (BSL-3) lab in person—an extremely restricted facility for obvious reasons, most notably because it’s where some of the planet’s deadliest pathogens are studied, including coronaviruses and anthrax.

In late October the members of the biodefense master’s program at the Schar School got a rare inside look at George Mason University’s Biomedical Research Laboratory on the Science and Technology Campus in Manassas, Virginia. The bottom-to-top tour of the 52,000-square-foot, $50 million building was possible because the nondescript structure in a far corner of the campus was emptied of external scientists, internal faculty, and authorized students for two weeks of cleaning, repairs, training, and equipment recalibration.

The two-hour tour was led by Farhang Alem, interim director of the lab, and Rachel Pepin, director of research operations at the lab. The students were joined by biodefense program director and associate professor Gregory Koblentz as they examined the hardware that makes the safe study of deadly diseases possible.

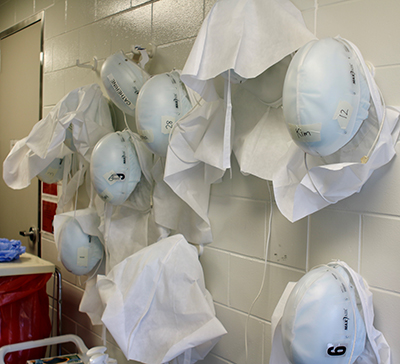

Mason’s BSL-3 lab was built in 2010 and “went hot,” in Pepin’s words, in 2012. It was funded with a $25 million grant from the National Institutes of Health and a matching grant, plus the land on the campus, provided by the university. The building has three levels, but only the ground floor contains the labs with movie-ready “gloveboxes,” benches, and cabinets for handling the pathogens, airtight sally ports to prevent contamination between hallways and labs, and the locker rooms where researchers change into the powered air-purifying respirators that are part of the protective equipment required when using the lab. The top floors are devoted to a vast array of equipment for air handling, cooling, and crucial safety functions.

There are also offices on the lower level for the staff of 15 that keep the lab running. Some 30 Mason students are actively using the facility at any given time.

“In the biodefense program we focus on blending theory with practice, and practice is all about the nuts and bolts,” said Scott Wollek, an adjunct teaching health security preparedness who also took the tour. “Visiting the [BSL-3 lab] provides an opportunity to experience the complexity of biocontainment labs and understand the research they do in a way that can't be replicated in a classroom.”

Biodefense master’s student Theresa Hoang agreed. Even though the medical lab scientist has experience in BSL-2 and -3 labs, “the tour impressed me, especially the PPE that the workers would have to wear,” she said. “They described how they would do the donning and doffing and how every door in each room that you enter would need to be completely closed, so that the negative pressure is maintained. And there were many doors.”